- Home

- Claire Berlinski

There is No Alternative Page 8

There is No Alternative Read online

Page 8

. . . Economically, Britain is on its knees. It is not unpatriotic to say this. It is no secret. It is known by people of all ages. By those old enough to remember the sacrifices of the war and who now ask what ever happened to the fruits of victory; by the young, born since the war, who have seen too much national failure; by those who leave this country in increasing numbers for other lands. For them, hope has withered and faith has gone sour. And for we who remain it is close to midnight.

. . . the world over, free enterprise has proved itself more efficient, and better able to produce a good standard of living than either socialism or communism. [But] . . . The Labour Party is now committed to a program which is frankly and unashamedly Marxist.

. . . let’s not mince words. The dividing line between the Labour Party program and communism is becoming harder and harder to detect. Indeed, in many respects Labour’s program is more extreme than those of many communist parties of Western Europe.

. . . Between the pair of them, Sir Harold [Wilson] and Mr. Callaghan and their wretched governments have impoverished and all but bankrupted Britain. Socialism has failed our nation. Away with it, before it does the final damage.

. . . We can overcome our doubts, we can rediscover our confidence; we can regain the respect of the rest of the world. The policies which are needed are dictated by common sense.

. . . Of course we’re not going to solve our problems just by cuts, just by restraint. Sometimes I think I have had enough of hearing of restraint. It was not restraint that brought us the achievements of Elizabethan England; it was not restraint that started the Industrial Revolution; it was not restraint that led Lord Nuffield to start building cars in a bicycle shop in Oxford. It wasn’t restraint that inspired us to explore for oil in the North Sea and bring it ashore. It was incentive—positive, vital, driving, individual incentive. The incentive that was once the dynamo of this country but which today our youth are denied. Incentive that has been snuffed out by the socialist state.

. . . Common-sense policies must, and will, prevail if we fight hard enough.

. . . I call the Conservative Party now to a crusade. Not only the Conservative Party. I appeal to all those men and women of goodwill who do not want a Marxist future for themselves or their children or their children’s children. This is not just a fight about national solvency. It is a fight about the very foundations of the social order. It is a crusade not merely to put a temporary brake on socialism, but to stop its onward march once and for all.

. . . As I look to our great history and then at our dismal present, I draw strength from the great and brave things this nation has achieved. I seem to see clearly, as a bright new day, the future that we can and must win back. As was said before another famous battle: “It is true that we are in great danger; the greater therefore should our courage be.”47

The last line is from Shakespeare, whose achievements, as she points out, were not the product of restraint. The words are spoken by Henry V on the eve of the victorious Battle of Agincourt.

Shakespeare, the Crusades, great and brave things, the fruits of victory and common sense—all of this, she claimed, was her rightful inheritance. They were Britain’s rightful inheritance. But the Marxists were scheming to cut her children out of the will.

They would not succeed.

It is all like this, in the archives. Guilt, shame, decay, decline, immorality, wickedness, a once-great nation brought to its knees, double-doses of socialism. These words are counterpoised against descriptions of Thatcher as a woman of old-fashioned virtue and common sense who will do what is proud, patriotic, self-respecting, honorable, and right.

Do you find the language of these documents shocking? I confess that I do. I completely agree that socialism is corrupting. I hate communism, too—I loathe it. But to see these overwrought sentiments emerging from a people famed for their reserve, irony, and understatement leads me to suspect that Bernard Ingham was on to something when he remarked that “the British pride themselves on being a wonderfully even-tempered and decent people, but once they embrace a doctrine, they can become quite, quite extreme.”

4

Diva, Matron, Housewife, Shrew

Pierre, you’re being obnoxious. Stop acting like a naughty schoolboy.

—THATCHER TO CANADIAN PRIME MINISTER

PIERRE TRUDEAU, 1981

It is all very well to hate communists, but self-righteousness and rage are not politically appealing qualities in and of themselves. Thatcher had charisma, too—feminine charisma—and this is what made her message effective.

If history is any guide, it is exceptionally hard to make femininity work to advantage in a political career. Several strategies are available to those who try. Hillary Clinton, for example, intimates that whereas she may have no obvious feminine qualities to speak of, a vote for her is a vote for feminism itself, a principled stand in favor of sexual equality. Some, like the French politician Ségolène Royal—or the woman she so resembles, Eva Perón—play the role of the mystical hysteric. Some exploit their status as wives or daughters of prominent politicians—Hillary Clinton and Eva Perón, again, or Indira Gandhi, Nehru’s daughter. It helps considerably if the husband or father has been martyred. Sonia Gandhi followed her martyred husband. Benazir Bhutto followed her martyred father—and followed him, sadly, all the way to martyrdom.

In her success in capitalizing upon her femininity, Margaret Thatcher had no equal. Yet she adopted none of these strategies. She had no use for feminism and no use for women, either—only one served in her cabinet, and only very briefly. By my count she inhabited, shiftingly and at will, at least seven distinctly female roles:1. The Great Diva

2. The Mother of the Nation

3. The Coy Flirt

4. The Screeching Harridan

5. Boudicea, the Warrior Queen

6. The Matron

7. The Housewife

These roles deserve a close inspection. They were the tools she used to make her revolution happen.

I am visiting Charles Powell, Thatcher’s foreign and defense advisor from 1983 to 1990, at his tastefully appointed Georgian mansion on Queen Anne’s Gate, overlooking St. James’s Park. Powell descends from one of the knights who carried out Henry II’s orders to assassinate Thomas Becket. Like his ancestor, Powell is a knight. His full title is the Baron Powell of Bayswater of Canterbury in the County of Kent. He is a member of the House of Lords. Some people in Britain take these titles very seriously; some don’t; some make an ostentatious point of pretending not to. I am not sure which category he falls under, so when I introduce myself, I hesitate.

His last name presents another challenge. I have been told that he pronounces it Pole, but his brother Jonathan pronounces it Powell , to rhyme with towel. His brother was Tony Blair’s chief of staff. I am not sure what to make of this but suspect it is evidence for the claim that they are all Thatcherites now. Left-leaning British newspapers, unable to find much to distinguish between the brothers politically, have fixated on their names; they declare the pronunciation Pole pretentious. As I offer him my hand, I worry that I’ve gotten it mixed up. Which is the pretentious pronunciation again, and which one is he?

“So nice to meet you,” I say.

“And you,” he replies.

The interchange offers no clues about his name. His part of it suggests that he may well be uncertain of mine.

Powell was Thatcher’s closest advisor, “the second most powerful figure in the Government,” writes her biographer John Campbell, “practically her alter ego.”48 Powell and American National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft shared a secure line to each others’ phones. Scowcroft called Powell directly when he needed to talk to Britain. Powell was, according to Scowcroft, “the only serious influence” on Thatcher’s foreign policy.49 Powell’s status as the prime minister’s pet was greatly resented. Alan Clark, Thatcher’s defense minister and an infamously indiscreet diarist, recalls the vexation of another close Thatcher advisor, Ian Go

w, who lamented “the way the whole Court had changed and Charles Powell had got the whole thing in his grip.”50 The ever-irritable Nigel Lawson, Thatcher’s chancellor, was equally dismayed by Powell’s overweening influence: “He stayed at Number 10 far too long.”51 Everyone—whether or not they liked him—agrees that Charles Powell is a highly intelligent man.

Given the descriptions I have read of him, I am expecting to encounter a suave, gregarious personality, but instead I find him a man of subdued affect. He is correct and courteous, but as we speak, I worry that I am failing to draw him out. Only later, when I transcribed the interview, did I realize that the language he used to describe the former prime minister was passionate.

“Tell me about your first impression of her,” I say. “I understand that you first met her when you were waiting with your wife for the by-election results in Germany—”

“That’s right, yes—we were in the embassy in Germany. She came out to see Schmidt and Kohl.52 She was quite recently elected in the Opposition. Well, I think it was of this tremendous energy and zest, we’d got pretty used to this procession of rather dispirited politicians, of all three parties, trooping through Germany lamenting Britain’s decline and so on, and here, suddenly, there was this woman, of whom we knew little at the time, who seemed to believe it could all be changed. It just needed her to be in power to bring about this tremendous change. It was invigorating.”

Energy, zest—everyone uses those words. She famously required no more than four hours of sleep at night. “She hated holidays,” Powell recalls. “She loathed holidays; she didn’t like weekends, because they were a bit of an interruption, but that was all right because she could pretend they didn’t exist by continuing working at Chequers, and making some of the rest of us work at Chequers, but holidays, after two days she was on the telephone, looking for excuses to come back to London.”53

“Would you describe the environment around her as tense?”

“The environment around her was boiling. A permanent state of everything sort of red hot. Like some kind of lava coming out of a volcano. It really was.”

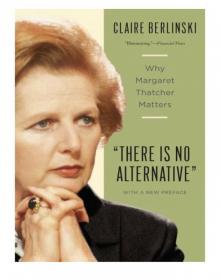

This image of Thatcher, visiting the White House in 1979, conveys the old-fashioned movie-star glamour she could project when it suited her purposes. If you did not know this was the new prime minister of Britain, you could easily imagine this woman sweeping regally into the Kodak Theater to collect an Oscar for lifetime achievement.

“Did you like being around that?” The man before me is sedate, his hands folded primly in his lap. It is hard to imagine that a boiling environment would be to his taste.

“Well, it was pretty invigorating, but really tiring.”

I’ll bet.

I ask him to tell me more about the way Margaret Thatcher looked to him, back in those early days. “Her posture was always upright,” he says. “She was very, very stiff-backed and upright, and she was always very tidy as well. A lot of British politicians are very sloppy, in their dress and so on—I don’t want to actually name any names or be discourteous, but you can probably think of quite several, female as well as male. But she was always meticulous in her dress, and perhaps some of her earlier styles look a bit fussy now, but once she got into the power-suit dressing it was all part of it. She was really—you’ve got to think in terms of Margaret Thatcher Productions, almost, I mean there were the policies and the rhetoric, but there was also the hair, the dress, the lighting, and everything. She could have tremendous dramatic effect on the platform, whether at a party conference speech or a speech to a joint session of the U.S. Congress. It was all packaged. It was almost like a great diva, giving a performance.”

He is right. Margaret Thatcher often seemed like an exceptionally gifted actress playing the role of Margaret Thatcher. On television, she fills the screen. The eye is ineluctably drawn to her, so that everything and everyone else in the frame is dwarfed by comparison. Hollywood executives call this quality It. Marlon Brando had It, and so did Marilyn Monroe. But neither of them had nuclear weapons.

Let’s look at one of those Margaret Thatcher Productions in slow-motion. Part of it is on YouTube, in a clip titled “Margaret Thatcher Talking about Sinking the Belgrano.”54 During the Falklands War, Britain declared a two-hundred-mile exclusion zone around the islands, warning that any Argentine ship within the zone was subject to destruction. The Argentine cruiser Belgrano was outside this zone, sailing away from the islands. Thatcher or-dered it sunk nonetheless. The attack killed 323 Argentine sailors. An outcry over the carnage ensued, in Britain and abroad; some charged that this was a war crime. Whatever you may think about the sinking of the Belgrano, do note this: The Argentine navy thereafter refused to leave port.

Here is Thatcher, responding to critics who have charged her with obfuscating the circumstances leading to the decision to sink the Belgrano. She is in the television studio with interviewer David Frost, an ordinarily articulate man who is not known for backing away from power but who in her presence appears oddly goofy. Her hair is sprayed into a stiff golden helmet; not a strand is out of place. Her rouge is flawless. Pale lipstick highlights a mouth that on another face might be described as sensuous. She is wearing pearl earrings; the broach on the lapel of her stern navy suit complements her blouse. The effect, as Powell said, is immaculately tidy.

David Frost: On that day, when the Government said it changed direction many times, it only changed direction once to go back home and a 10-degree difference to get closer to Argentina—

Prime Minister: A ship is torpedoed on the basis that if wherever she is she can get back to sink your ships in reasonable time, you do not just discover ships on the high seas and keep track of them the entire time. You can lose them. You can lose them. I would far rather have been under the attack I was for the Belgrano than under the attack I might have been under for putting the Hermes or Invincible in danger, and if ever you think that governments have to reveal every single thing about ships’ movements, we do not! And if I were tackling—

DF: No, but I mean, the reason people get—

Prime Minister:—in charge of a war again, I would take the same decision again . . . Do you think, Mr. Frost, that I spend my days prowling round the pigeonholes of the Ministry of Defense to look at the chart of each and every ship? If you do you must be bonkers!

DF: No! Come back to the—

Prime Minister: Do you think I keep in my head—

DF:—when you said to Mrs. Gould55—when you said to Mrs. Gould on the election program before the election in ’83 that it was not sailing away from the Falklands, you had known from November ’82 that it was!

Prime Minister: What I said to Mrs. Gould was, “If you think that I know in detail the passage of every blessed ship I cannot think what you think the Prime Minister’s job is!”56

You may tune in on YouTube to see the rest. Study the voice: Like a trained stage actress, she projects from the chest and uses the full range of her vocal register. Her body remains still; she does not fidget or shift or even gesture. Note the varied rhythm of her speech—one moment slow and deliberate, the next insistent and percussive. “What I know, Mr. Frost,” she says—and she pronounces his name, Mr. Frost, as if a Mr. Frost is some thoroughly disgusting species of bug—“is that the ministers have given the information to the House of Commons. They said that one thing was not correct. I was the first to say, ‘Right, give the correct information .’ And the correct, and deadly accurate information was given.” The word “deadly” flows easily from her tongue. She is leaning forward, intense, alert. Her eyes are blazing. You are looking at a woman who has given the order to kill 323 young Argentine men, and her glowing complexion suggests that this has not troubled her sleep one bit. Indeed, she looks as if she has had an exceptionally good night’s rest.

“But I do not spend my days,” she continues—in response to a question he has not asked—“prowling around the pigeonholes of the Ministry of Defense looking at the precise course of action.” She says I as if the I in ques

tion is something magnificent, and the very hint that such a vital magnificence—Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the human embodiment of the British people and their destiny!—would do something as lowly as prowl (never mind that Mr. Frost never said this) is contemptible. There is now something like a bat squeak from Mr. Frost. “One moment!” she pronounces, lifting an imperious finger. “One moment!”

Mr. Frost tries haplessly to get a word in, fumbling with his papers. “Woodrow Wyatt says you only respect people who—”57

“One moment,” she demands.

“Yes,” he says meekly and falls silent. Her voice is lower now, and all the more menacing for it. Given her expression you would not be entirely surprised to see laser beams shoot from her eyes and vaporize this disgusting Mr. Frost, bringing the death toll to a salutary 324. “That ship”—she says this slowly, her mouth narrow, her voice full of controlled fury and contempt—“was a danger to our boys.”

Our boys: These are in fact men she is talking about, every last one of them over the age of majority and armed with fearsome weapons, and the use of the word “boys” sounds at once fiercely maternal—a tiger protecting her cubs—and intensely patronizing. Those boys are our heroes, as all right-thinking men and women know, and you, Mr. Frost, are not fit to shine their shoes. But they are still boys, just as you, Mr. Frost, are a silly stripling. The lot of you—boys. But you are my boys, and that is why despite your childish foolishness, I shall protect you and set you on the right course. “That’s why that ship was sunk,” she says. “I know it was right to sink her.” A pause. Mr. Frost has gone mute. “And I would do . . . the same . . . again.”

Fade to black.

Lion Eyes

Lion Eyes Menace in Europe: Why the Continent's Crisis Is America's, Too

Menace in Europe: Why the Continent's Crisis Is America's, Too Loose Lips

Loose Lips There is No Alternative

There is No Alternative